The India-China Border Dispute

|

| Sino-Indian Border Conflict—a conflict that's lasted for more than seven decades |

Two Asian Giants: India and China

India and China—the two giant Asian economies, are both ancient civilisations that evolved as modern republics in the mid-twentieth century. From the warring states within, to the whip of imperial colonialism; both have had a long history of wars and subjugation. This was followed by the rise of nationalism and a push for self-dependence.

Home to one-third of the world’s population, both nations have since emerged as rising powers with burgeoning economies (2nd and 5th largest, respectively, as per GDP numbers) in the last decade and continue to grow.

Militarily strong, both nations are nuclear-armed and aggressively expanding their conventional arsenal, vying for influence not just regionally but on a global scale. In fact, China on that front has most certainly leapfrogged - leveraging its human capital, industrial boom, and, more importantly, trade as a means to make inroads and simultaneously increase its sphere of influence.

|

| Troops deployed along the Sino-Indian frontiers (est.) | Source: Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs |

Boundary Disputes and Expansionism

The phenomenal rise of China in recent years and its arrival on the global stage as a mighty power has made Beijing more and more assertive with its territorial claims. Similar to its neighbour India, China is embroiled in boundary disputes with many of its other Asian neighbours, including over the Senkaku Islands (Diaoyu) with Japan in the East China Sea or the larger, more contentious South China Sea dispute that involves competing for claims from many nations.

China, however, claims territory entirely based upon a nine-dash line. In fact, to assert its sovereignty, it has even developed artificial islands and maintains a strong naval presence. When it comes to the credibility of these claims, there is certainly the question of Beijing’s cartographic subjectivity. Moreover, these disputes are not merely historical claims or a fight over resources or nationalistic glory. Rather they have a clear strategic and geopolitical aim. For instance, consider this: One-third of the world’s maritime shipping passes through the South China sea.

In so far as India is concerned, clearly, the Chinese claims, like the claim line itself, have changed in the past. Beijing’s revisionist tactic involving creating buffer zones and then gradually occupying them has, in the past, used transgression as a pretext. Now whether or not Beijing wants to be a kingmaker in the region or is simply miffed with New Delhi’s changing stance, the fact remains that the simultaneous growth and ambitions of the two fast-growing economies are causing dangerous friction in their relations.

The aspirations of billions on either side, the political compulsions, and moreover the changing geopolitical and global landscape seem to be reigniting the age-old border conflict. The increasing tensions along the LAC and the two major conflicts in the last three years (2017-2020) reaffirm the same. It now seems that the delicate status quo is being altered on an as-and-when-needed basis.

Indian Claims

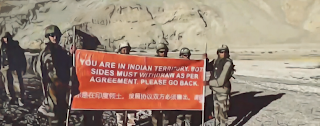

|

| Indian Soldiers holding banner warning the Chinese Troops |

Currently, China is in occupation of approximately 38,000 sq km (14,700 sq miles) of Indian territory in the Ladakh region. This includes the Aksai Chin plateau, which was taken over by China in the 50s and additional territory that was later seized as the spoils of the 1962 war. In the aftermath of the war, the China-Pakistan Boundary Agreement of 1963 was also inked, and Pakistan ceded 5,180 sq. km. of territory in the POK or Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (a region disputed between India & Pakistan) to China. This ceded territory, the Shaksgam Valley, serves as a vital link between Xinjiang and Tibet, and by securing it, China also managed to push its territory further south towards Ladakh (erstwhile J&K State).

Additionally, Beijing has invested heavily to the tune of USD 60 billion in the ambitious CPEC (China-Pakistan Economic Corridor) project—another friction point in Sino-Indian relations. The corridor (a work in progress since 2015) passes through the Pakistani-held J&K territory (POK) and connects the overland maritime routes of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), of which CPEC is a part to Pakistan’s Gwadar Port. Overall this not only threatens Indian territorial claims but also considerably increases the Chinese influence in the region. At the same time, it also raises Beijing’s stakes in the larger and ongoing Kashmir dispute between India and Pakistan.

Furthermore, China to date also doesn’t recognize the north-eastern Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh bordering Tibet and claims it as its own.

|

The Northern Frontiers and conflict zones along the LAC in Ladakh Region. |

History of the Sino-Indian Conflict

Vague historic references, treaties inked or imposed during British rule, claims and counter claims, differing perceptions and overall a lack of consensus, have all contributed to the present state of tensions along the unsettled India-China boundaries. A legacy inherited from outgoing British Rule and left for the future generations to deal with.

Both nations share a border more than 3,488-km (2,162 miles) long with overlapping territorial claims at several places – In the west passing through the union territory of Ladakh (formerly the state of Jammu & Kashmir) it’s demarcated as the Line of Actual Control (LAC). The LAC moving through the Central Sector separates neighbouring Himanchal Pradesh and Uttrakhand state of India from China's Tibet Autonomus Region (TAR). Further along the Eastern Frontiers of Arunachal Pradesh (erstwhile NEFA or North East Frontier Alliance) bordering the TAR, it’s referred to as the McMahon Line. At some places the boundary is settled like the Sikkim border, and this marks the International Boundary. But it is mostly along the vast stretches of these long, unsettled, or poorly demarcated boundaries, across the most difficult, desolate and high-altitude terrains, that there exists a history of conflicts. And since the borders are not clearly marked or defined, the patrols often find themselves in the grey zones or trespassing into each other’s territories – What is often described as transgression. Confrontations then became inevitable. From mere push and shove, minor scuffles to even bloody conflicts. Despite defined set of rules for amicable solution, things do get escalated resulting into serious confrontations.

Though in the last few decades, these have mostly been sorted out without much ruffling of feathers in the higher echelons or the show of strength on the ground. But to say that friction doesn't exist would certainly be an understatement, especially in light of the brutal escalations like the incident of June 2020. It must be noted that as the LAC fringes mountains, valleys, lakes and plateaus, it's often impossible to pin-point the perceived or loosely agreed upon boundaries.

Briefly: Aksai Chin Boundary

British Surveyor William Johnson in 1865 proposed the Johnson Line that placed Aksai Chin in Kashmir region, following Kunlun alignment. Intelligence officer John Ardagh in 1897 redrew the line. The British again proposed the McCartney-MacDonald line in 1899, that placed much of Aksai Chin in China following Karakoram alignment. The Qing administration never responded to the proposal. More changes were made by the British in 1905, 1912 and finally in 1927. These were not communicated to Beijing.

|

| The disputed frontiers between India and China |

Briefly: McMahon Line

McMahon line represents the de-facto border between Tibet Autonomus Region and Arunanchal Pradesh. The demarcation agreed upon during the tripartite Shimla Conference of 1914 involved representation from Tibet, China and Britsh India. The negotiation for the same lasted from Novem¬ber 1913 - July 1914, and intialed on April 27 1914, by the three plenipotentiaries. Later amended but never ratified by Beijing. However Beijing never opposed or objected to it either.

The 50s Era

Under the leadership of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, the Republic of India for most part maintained a warm and cordial relation with China. India was the first non-communist nation and the second nation after Soviet to recognise People’s Republic of China (PRC). India also enthusiastically supported Chinese elevation to the P5 in the UN Security Council. The PRC under Mao Zedong’s leadership had made its intention of border settlement known right away as it seized control of erstwhile Sinkiang (Now Xinjiang) overlooking the Indian Ladakh region. The Great Leap on the ground followed China's annexation of Tibet (1950), changing not just the geography but also the geopolitics of the region, all within months of its independence.

Overnight, the strategic move removed the buffer zone between India and China which until then from an Indian perspective had kept the Chinese at bay. India decided to stay put despite a tacit understanding of support from the United States and desperate call for help from Tibet. Even the British India had known the relevance of this buffer zone and hence left it as such. Although it was not the then weakened Qing Emipre that they were concerned about but rather the Great-Games with Russia.

In the following years tip-toeing Mahatma Gandhi’s idealism, Prime Minister Nehru championed the Panchsheel Treaty (April 29, 1954) with non-interference as one of its five key tenets. There by legitimising Beijing's occupation without seeking any sort of settlement on the new frontiers. Friendship and peace was the call. The colloquial catch phrase back then, "Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bhai" or Indians and Chinese are brothers hence stood for more than just symbolism.

Things however began to go south as India began manning its border and with the Chinese capture of India's Aksai Chin plateau in the Ladakh region, the cracks were out in the open. While the Indian Government kept napping, the Chinese had completed a strategic Highway (G219) through Aksai Chin linking Tibet with Xinjiang. Although China had officially announced the completion of the G219 highway in September 1957, Indian government was slow to respond. Even the reconnaissance party that was finally dispatched in the following year was taken into custody by the Chinese troops. On August 28, 1959, Prime Minister Nehru finally made a statement on the issue in the parliament that lacked in the resolve. Clearly even though India at that juncture was beginning to grow wary of its neighbour, it had conceded to the Chinese territorial expansionism vis a vis Aksai Chin. But the public sentiments had begun to shift and the domestic politics henceforth requisited action.

Forward Policy

To some extent India initially did pre-empt the dragon by adopting what was called the Forward Policy that aimed at flagging the borders and setting outposts. With inputs from the Intelligence Bureau (IB) and assistance from the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), and the Assam Rifles, the policy was a pragmatic approach to counter the Chinese expansionist designs. Unfortunately, neither was it well planned and nor aptly executed. Perhaps its biggest shortcoming was the underlying assumption that Beijing would not react by force especially to what it would consider as Indian transgression, since clearly both countries had their own assumptions on where the perceived boundary lay.

Tibet Unrest and Spillover

A failed uprising in Tibet (1959) against the Chinese rule led to Tibetan spiritual leader Dalai Lama seeking shelter in India (Mar 1959), who has since been living in exile in India. India’s support to Dalai Lama further deteriorated the already fragile Sino-Indian relationship and the hardening of the Chinese stance.

Same year China put forth what is referred to as the 1959 claim line to renegotiate borders in Ladakh; essentially imposing newer claims. Prime Minister Nehru however showed no interest and was unwilling to even discuss the issue. In August, 1959, the killing of an Indian soldier in an armed clash at a point called Longju along the McMahon Line was the writing on the wall of what was to follow. Russian Premier, Nikita Krushchev’s reprimanding the Chinese leadership had little effect on the course of events. Shortly thereafter a more serious clash on 21st October at Kongka La Pass (Ladakh Region) resulted in casualties on both sides. The situation along the borders had clearly become extremely volatile in a matter of months.

Turbulent 60s

In the aftermath of Longju and Kongka La incidents more conflicts followed. Lt Gen H S Panag, former GOC-in-C, Indian Army Northern Command, aptly sums the situation at this crucial juncture, “the border clashes and casualties led to immense pressure from the public and in Parliament. Nehru lost his nerve and abandoned a fairly successful strategy. All his subsequent actions were panic-driven, tactical and bereft of strategic thought. Diplomacy was abandoned.

The pragmatic frontier-flagging ‘forward policy’ adopted until then was replaced by a more aggressive ‘forward policy’, which actually became ‘forward movement of troops’, to call the Chinese bluff. Less by design and more by default, Nehru blundered into a military confrontation on an unfavourable terrain and with an army that was unequal for the task. Rather than calling the bluff of the Chinese, our own bluff was called.” The Times, Asia correspondent, Neville Maxwell had termed the forward policy as Nehru's covertly expansionist policy.

The 1962 War: A Wound That Festered

In September, 1962, a confrontation at the newly setup Dhola post north of the McMahon line got escalated. The border situation had long been tense. When Prime Minister Nehru ordered the Chinese be pushed out of India’s territory. China saw it as a belligerent provocation and a justification. As friction grew and the early attempts of what seemed to be diplomacy failed, both nations fought a brutal war (21st Oct -21st Nov 1962). One that India had neither expected and nor was prepared or equipped to handle. Chinese on the other had come-in well prepared and with sufficient and credible intelligence launched a massive dual offensive along the NEFA and Ladakh region and quickly proved superior. Both sides did suffer heavy casualties in the war.

While the inquiry report (Henderson & Brooks) on India’s 1962 debacle till date remains classified, it’s no secret that the fallen were actually failed by the leadership. The Chinese eventually withdrew declaring a unilateral cease fire beginning November 21st, 1962. The withdrawal in Western Sector however followed further encroachment in-line with the Chinese 1959 claim line that eventually became the Line of Actual Control and a de-facto border. The PRC had thus achieved the objective of not just removing the Indian border posts which they believed were on their side of the claim line but simultaneously gained new territory in the process.

Nathu La & Cho La Clashes

The two countries engaged in yet another armed conflict in 1967 and this time the Chinese PLA got a heavy pounding at Nathu La (Sept 11th) and Cho La (Oct 1st) along the border of Sikkim (then an Indian protectorate) and China's Tibet Autonomous Region. Both sides suffered multiple casualties in the conflicts that started with Chinese objection to Indian troops laying fences along the border.

|

| The boundary expansion by China post-1962 war |

Clashes of 70s and Calm of 80s

The last of the bloody conflicts between the two countries took place on October 1975 when Chinese PLA troops ambushed an Indian patrol in Arunachal Pradesh’s Tulung La sector and shot four soldiers dead. Following the incident the two countries refrained from armed conflicts. They did however come close to one in 1986 at the Sumdorong Chu Valley bordering the Tawang district, Arunachal Pradesh and Cona County, Tibet Autonomus Region. Troops were deployed from both sides. It seemed as if the north-eastern frontier were turning volatile once again. However, senses prevailed and the tensions eased off without a further escalation. Situation along the border remained more or less peaceful along the frontiers in the following decade.

The Lull and the Peace Process

The Sino-Indian relations more or less remained frozen after the 1962 War and were finally revived in 1976, when diplomatic activity restarted. In the next few years efforts were made from both sides on political and diplomatic level to improve relations. Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi's Beijing visit in 1988 was another effort in that direction. Realising the need and urgency for peace various agreements followed in the 90’s. Simultaneously there was also a push to improve trade relations, which has since been booming. In fact China in recent years has surpassed others becoming India’s biggest trading partner.

Agreements for peace & tranquility along the borders:

- September 7th, 1993: Agreement on Maintenance of Peace and Tranquillity along the LAC. The agreement stressed that the two sides would reduce their forces along the LAC and that the “extent, depth, timing, and nature of reduction of military forces” would be determined through mutual consultations.

- November, 1996: Article 3 of the agreement specified that the major category of armaments such as tanks, infantry combat vehicles artillery guns, heavy mortars, surface-to-surface and surface-to-air missiles would be reduced with the ceilings to be decided through mutual agreement. Also emphasising, "neither side shall open fire, conduct blast operations or hunt with guns or explosives within two kilometres of the Line of Actual Control". Both 1993 and 1996 agreements were a part of larger confidence building measures (CBMs) critical to peace and tranquillity along the LAC.

- June 2003, the Special Representatives (SRs) mechanism for resolution of the boundary dispute was also set up. As of December 2019, the SRs have had 22 rounds of talks, although not much has been achieved on that front.

- April, 2005: Agreement on political parameters and guiding principles for settlement of the boundary dispute.

- January, 2012: Agreement on the establishment of a Working Mechanism for Consultation and Co-ordination (WMCC) on India-China border affairs.

- October, 2013: Border Defence Cooperation Agreement.

Further Conflicts:

The 2013 Depsang Standoff

Despite minor confrontations over perceived boundaries the Sino-India frontiers mostly remained peaceful until Beijing decided to alter the status quo once again.

On April 15, a Chinese PLA contingent intruded almost 19 km at the mouth of Depsang Bulge, 30 km south of Daulat Beg Oldi near the LAC in the disputed Aksai Chin region. Indian forces responded to the Chinese presence by setting up their encampment just 300 metres away.

Negotiations between the two sides ensued and lasted nearly three weeks. On 5th May, an agreement was reached after which both sides withdrew. As part of the resolution, the Indian military agreed to dismantle some military structures 250 km away in the Chumar sector, which the Chinese had perceived as threatening.

The 2017 Doklam Standoff

It was in June 2017 when the two Asian nations locked horns at Doklam in the neihbouring Bhutan. The conflict started with Indian intervention to a road construction by Chinese in a disputed area in Bhutan and eventually resulted in a full-blown confrontation following a scuffle between the troops of both sides. This was perhaps the more serious of confrontations in decades, as both sides initially indulged in war of words and show of stregth, but later large number of troops were rushed to the site from both sides. The troop build-up the political rhetoric and 24/7 warmongering of mainstream media, almost made a war looked inevitable. However diplomacy paved in and senses prevailed. Ultimately, 73 days later the deadlock was broken and disengagement took place.

The 2020 Galwan Conflict

Amidst the testing times of a one of its kind pandemic the Sino-India frontiers once again began to heat-up. May 2020, the soldiers of both sides exchanged physical blows at Nathu La, Sikkim, along the eastern frontiers. Simultaneously the confrontations also took place in the Ladakh region.

In May, media reports with satellite imagery also surfaced revealing the Chinese PLA forces had put up tents, dug trenches and moved heavy equipment several kilometres inside Indian territory. Simultaneously incursions along other conflict areas were reported. The move was a clear violation of all earlier agreements, and with it China unilaterally decided to change the status quo, thereby provoking a conflict. Beijing on its part accused Indian side of transgression. Efforts were made to defuse the tensions. On June 6th, senior military commanders reached an agreement on de-escalation and disengagement along the LAC with ground commanders meeting regularly to implement this consensus. Despite the consensus however, a brawl ensued. More soldiers from both side joined in while some PLA troops came armed with nail studded clubs. A full-blown medieval war broke out with sticks, stones and the more lethal clubs at 14,000 feet in pitch darkness.

As soldiers fought along narrow ridge line at patrolling point-14, some even fell into the river below and were severely injured. The brutal clash lead to the death of 20 Indian soldiers of 16th Bihar Regiment, including the commanding officer and an unknown number of PLA casualties. The Indian Army officials had claimed around 43 Chinese were killed or seriously injured, citing radio intercepts and other intelligence. The Russian state media had later placed the casualty number at 45 (19 Oct 2020, TASS).

“Neither have they intruded into our border, nor has any post been taken over by them (China). Twenty of our jawans were martyred, but those who dared Bharat Mata, they were taught a lesson.”

- Prime Minister Modi on Galwan Incident (All-Party Meet, 19th June, 2020)

|

| Map highlighting the Chinese transgression during 2020 Galwan Conflict |

The Ladakh Standoff

Following the June clash both sides dug in their feet in Ladakh as China refused to restore the status quo ante that prevailed prior to April 2020, while India remained firm on its demand to de-escalate and disengage. The aftermath of the Galwan incident saw aggressive posturing from both sides as more troops and heavy artillery including tanks were deployed. Positions all across the LAC, especially conflict zones were being fortified. Yet again the war clouds seemed darkening the skies with ultimate showdown happening at the battleground Himalayas along the northern banks of Pangong Tso Lake. Despite several rounds of talks and multiple channels being sought to disengage and diffuse tensions, both sides kept hardening their stance while blaming each other of transgression and violating the consensus along the LAC.

Timeline of the Standoff

|

| Satellite imagery of the Chinese structures removed from the Pangong Tso |

End Note

In this age of globalisation, progress and development will not and cannot have a solitary existence. Political landscape and regional geopolitics will keep reshaping with rise and fall of the polity within. Old friends will grow weary and new alliances will keep on forging—triad or quad, it doesn't matter. Interests reign supreme, and would matter after-all. But under no circumstance should we be fighting other's war in our own backyard. Despite the mistrust that have long existed and the new wave of antagonism; peace, cooperation, and timely & amicable resolution of all existing issues can only be the way forward.

China is our neighbour and that fact is not going to change. We can never handle the dragon effectively unless we can look it in the eye; or in other words be on an equal footing, or at least close to. And that's not exclusive to military might but economic strength and diplomatic prowess too. Frontiers ultimately would have to settled but that can only be achieved through dialogue. Now whether or not good fences will eventually make good neighbours would ultimately depend upon the political will on both sides. End of the day belligerent nationalism, aggressive posturing etc are by and large mere tools of public perceptions often put in use by states. Now whether they slash or heal, or get used or exploited, is not a choice that's entirely their's.

Wars either way are no longer confined to the convention spaces; rather they are constantly being raged and fought in virtual spaces (cyber and electronic), as well as on economic front as trade-wars etc. And that is not going to change any soon as both economies continue to grow and aspire to leapfrog. End of the day, peace even if fragile, is in the best interest of people on both sides.

“We will never seek hegemony, expansion, or sphere of influence. We have no intention to fight either a cold war or a hot war with any country. We will continue to narrow differences and resolve disputes with others through dialogue and negotiation.”

- Chinese President Xi's 2020 UNGA Address

Comments

Post a Comment